In the first installment of Data Stewardship Common Issues, we covered five items that can be difficult to deal with. In this, the second and final installment, we’ll round out our “top ten” with another five items.

Training the stewards properly

Given how busy stewards are, it can be tricky to get them trained do discharge their responsibilities correctly. You will have limited time to accomplish the training, and you must be careful not to waste that time.

There are common mistakes that any training regimen can make: teaching the wrong skills, the wrong skill level, at the wrong time, to the wrong audience, and addressing the wrong objective. For example, it really does you no good to teach IQ concepts to stewards; instead, you should be teaching them how to properly perform their stewardship responsibilities.

Assuming you are sensitive to the mistakes you can make, what SHOULD you train steward to do? Here are a few of the most important skills you can teach:

- Provide background in Data Governance and Data Stewardship, and why Data Governance is important to the enterprise. You also need to educate the stewards on what the organization looks like, who chose them, and why.

- The roles and responsibilities of stewards, including identifying ownership of data elements, properly defining them and supplying the derivation and data quality rules.

- How meetings and Logistics will be handled.

- How to work with the tools, such as a Business Glossary, Metadata Repository, the Data Stewardship or Data Governance web site, any wikis you use, and how to understand lineage and impact analysis. As part of all this, it is important to draw the line between what the stewards are expected to do, and what IT is expected to do. For example, IT may be tasked with running the Data Profiling tool (which returns information about the data), but it is the stewards who analyze the results, discuss it with the subject matter experts, perform (in conjunction with IT) the root cause analysis – and formulate a remediation plan.

- How the improvement of data quality provides the driving force and ROI for Data Governance and Data Stewardship. In line with that, the stewards will need to know the basics of data quality, including formulating the data quality rules, figuring out what is going wrong (including most especially broken processes), and determining what to do about it.

Avoiding overwhelming the stewards

The best stewards are actively engaged with the business functions they represent, thus understanding the day-to-day intricacies, data and process issues, and impact of poor data quality. But that engagement (their “day job”) also means that they are generally pretty busy. It is critical, therefore, that stewardship duties not overwhelm them on top of everything else, and that demands on the steward’s time be limited.

The Chief Data Steward (the individual who runs the Data Stewardship Council) is critically important in monitoring these demands and prioritizing the requests for the steward’s time. This can be done by assessing the impact of decisions that are needed and asking the stewards for only those decisions with long-range impacts, as well as not beating small things to death. I recall an argument about a definition that dragged on and on and was consuming a lot of the steward’s time to finesse out the last bit of the definition. He finally complained that there were far more important stewardship decisions that needed to be worked on. The Chief Data Steward properly asked him for that list, discussed the importance of the things on it, and made a decision to leave the last bit of perfection out of the definition in favor of more important items.

Another crucial way to avoid overwhelming the stewards is not to have endless meetings. Most meetings (such as ownership discussions) can be with a focused audience where the stewards self-nominate to attend if they have an interest. Of course, to make that work, it is crucial that the stewards understand that NOT attending the meeting means they give up their say on that particular matter. At least, that is the theory, although in practice it is not quite that cut and dried. The other stewards (or the Chief Data Steward) may decide that a decision cannot be made without a missing individual’s input, in which case another meeting will need to be held. This does waste a bit of time, but overall, the steward’s time is used far more efficiently than if everyone attended every meeting.

Consider also whether a meeting needs to be held at all. A lot of issues and discussions can be held via collaborative environments, where the stewards are automatically notified that their input is needed, and they can then provide it at their convenience. This sort of collaboration is made more efficient by use of workflows and automatic reminders as well.

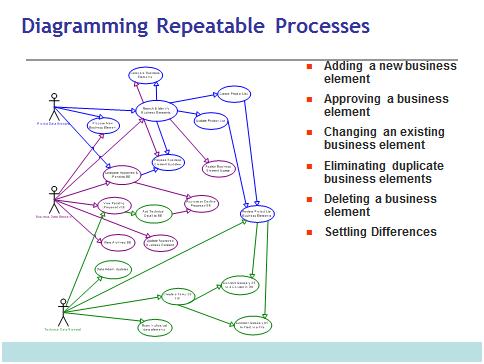

Not making it up every time

Stewardship needs to be efficient. Thus, you’ll want to institute a set of repeatable processes for such things as adding a new data element (including the approval process), eliminating duplicate elements, handling mis-use of existing data elements (such as by a project), verifying and validating lists of values, and so on. These repeatable processes should involve a specified set of roles or entries in a RACI (responsible, accountable, consulted, informed) matrix rather than specific individuals. This is because (for example), the Business Data Steward will be different depending on the data element(s) in question, but the roles should remain constant.

Ideally, the processes should be driven by workflows, with communication to the participants via email or some other electronic method as they receive new tasks. Having these workflows as part of your Metadata Repository makes a lot of sense, since many of the results will be stored in the repository. Further, modern repositories can store information such as who the data steward is for a particular data element – thus making it possible to automatically route the workflow through the correct individuals based on their roles.

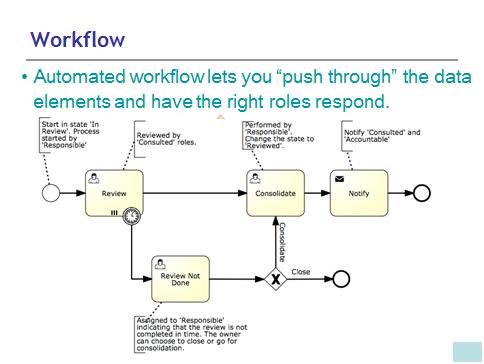

The workflow diagram below is from a modern business glossary product, and uses the RACI matrix for routing. Notice that is also implements a time-based trigger, so that if someone just lets their task sit for too long, it gets escalated automatically.

Making sure to communicate decisions to the appropriate Audience

One of the worst things you can do is keep people in your enterprise “in the dark” about developments and decisions in Data Stewardship. How will they know that certain key data elements have been defined, or that you’ve implemented a new business glossary, or that new policies and procedures must now be followed if you don’t tell them?

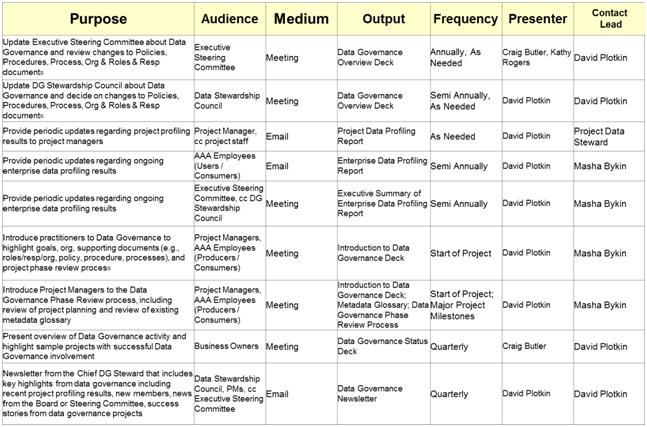

In order to ensure that people are well-informed, you need to develop a Communication Plan. The first part of the plan lays out the communication purpose, audience, communication medium, what sort of communication it is (e.g., PowerPoint slides, newsletter, etc.), frequency, and who is responsible for the communication:

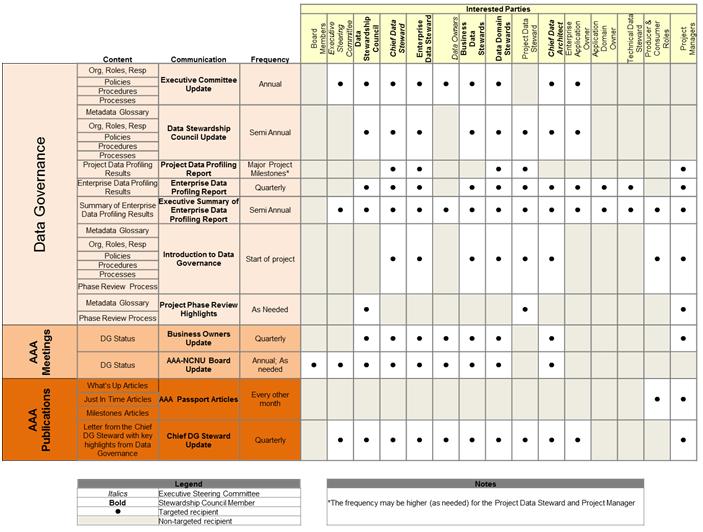

The second part of the communication plan takes the information and cross-references the various communications (and their frequency) against the interested parties, giving you the table you see below. I know you can’t really read it, but, for example, it says to bundle the content (org. roles, responsibilities; policies; procedures; and processes) into a communication entitled “Data Stewardship Council Update”, which is provided semi-annually to the Data Stewardship Council, Chief Data Steward, Enterprise Data Steward, Data Domain Stewards, and so on.

Measuring Data Stewardship “Success”

One of the biggest challenges for data stewardship is to measure its “success”. According to John Adler (in response to a question on LinkedIn), the metrics fall into two general buckets: a) metrics in support of the data program (business results) and b) metrics which indicate operational effectiveness of the data stewardship program.

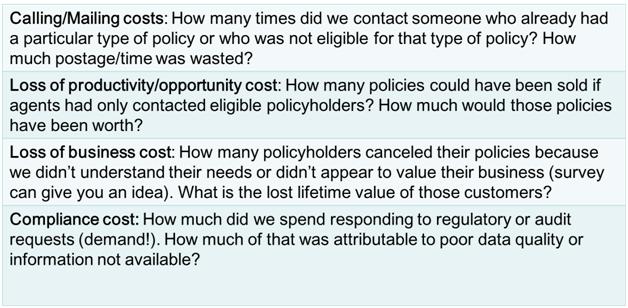

The business value side can be looked at in terms of increased revenue and profits (if you can get at those numbers), reduction of duplicate data (and data storage), increased productivity in the use of the data, reduced application development time and system integration costs, reduced time to market, fewer audit findings or compliance issues, and increased customer knowledge. As you can imagine, a lot of this can be hard to get at – but not impossible. With the proper measurements in place, you could go after these metrics as shown in the insurance example in the following table, where the quality of the customer data was wasting a lot of people’s time.

The operational metrics can measure things like a change in maturity level, reduction in disparate data sources, increase in the number of standardized definitions, how many business units have added data stewardship performance to their compensation plans, who are the most active contributors, how many people have been trained as stewards, and even how many times the metadata repository was accessed. Many of these items can be put on a progress scorecard of some sort.

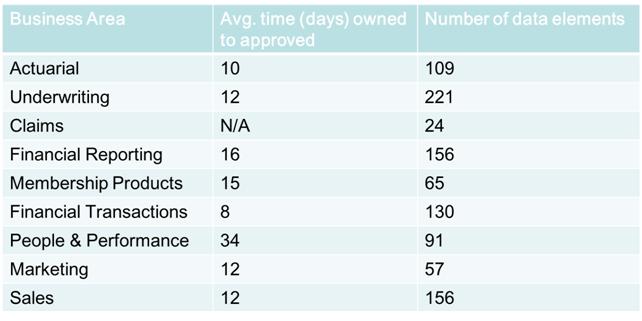

You could also consider making the work something of a “contest”, logging, for example, the number of data elements in “approved” status and the average time for them to get that way, as shown in the following table:

Summing Up

Hopefully, you won’t have to deal with all 10 of the items discussed here and in the first installment of this article. But after only 3 years setting up and running a Data Governance Program (including Data Stewardship), I had encountered them all. How do you think I can you advice on it?